import numpy as np

a = [1, 2, 3]

b = [4, 5, 6]

print(np.convolve(a, b, 'full'))[ 4 13 28 27 18]Let’s see how CNN actually does it’s magic!

CNN is short for Convolutional Neural Network, and convolution process as well as mathematical formula is the primary factor. Now, before we go deeper into the math, let’s check out how the convolution process works.

The convolution process refers to the action of mapping a filter called kernel across the image and performing a convolution mathematical operations to produce a feature map. It’s easier to show an animation of this:

In the animation above, we can see an image of 5x5 being convoluted with a 3x3 kernel resulting in a 3x3 feature map.

The convolution operation of two arrays \(a\) and \(b\) is denoted by \(a * b\) and defined as:

\[ (a * b)_{n} = \sum_{i=1} a_{i} b_{n-i} \]

Let’s see how this works in practice. Let’s say we have an \(A\) is \([1, 2, 3, 4, 5]\) and \(B\) is \([10, 9, 8]\). The convolution operation of \(A\) and \(B\) is:

\[ \begin{align} (a * b)_{2} &= \sum_{i=1} a_{i} b_{2-i} \\ &= a_{1} b_{1} \end{align} \]

\[ \begin{align} (a * b)_{3} &= \sum_{i=1} a_{i} b_{3-i} \\ &= a_{1} b_{2} + a_{2} b_{1} \end{align} \]

\[ \begin{align} (a * b)_{4} &= \sum_{i=1} a_{i} b_{4-i} \\ &= a_{1} b_{3} + a_{2} b_{2} + a_{3} b_{1} \end{align} \]

Confusing? Let’s watch the following video, it’s actually pretty simple.

In Python, we can use numpy.convolve to perform the convolution operation.

same parameter will make sure the output has the same length as the input.

valid parameter will make sure the calculation is only performed where the input and the filter fully overlap.

In the above example, the output is only calculated for \(1 * 6 + 2 * 5 + 3 * 4 = 28\).

How about 2D?

It’s possible to use numpy to perform 2D convolution operation, but it’s not as simple as 1D. We’ll use scipy.signal.convolve2d instead.

But that still doesn’t answer how does this process help detect edges ?

Note: To better illustrate, we prepare a spreadsheet for a quick simulation of Convolution: GSheet Link

So you can try it for yourself, it’s much easier using Google Sheet. Remember to make a copy for your own use.

Now, let’s put this knowledge into action:

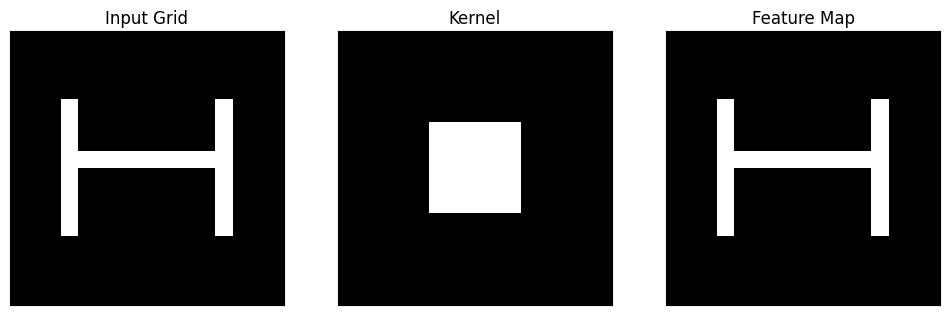

Let’s say we have a 16x16 grid containing a letter H. And we have a 3x3 kernel with the identity, meaning the only activated is the center number.

0 0 0

0 1 0

0 0 0import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from scipy.signal import convolve2d

def simulate_convolution(input_grid, kernel):

# Get the size of the input grid

grid_size = input_grid.shape[0]

# Perform convolution

feature_map = convolve2d(input_grid, kernel, 'same')

# Create a figure and subplots

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(12, 4))

# Plot the input grid on the left

axs[0].imshow(input_grid, cmap='gray')

axs[0].set_title('Input Grid')

# Plot the kernel in the middle

axs[1].imshow(kernel, cmap='gray')

axs[1].set_title('Kernel')

# Plot the feature map on the right

axs[2].imshow(feature_map, cmap='gray')

axs[2].set_title('Feature Map')

# Remove axis labels and ticks

for ax in axs:

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

# Show the grids

plt.show()

print("input_grid", input_grid, sep='\n')

print("kernel", kernel, sep='\n')

print("feature_map", feature_map, sep='\n')

# Create a 16x16 input grid with the letter "H"

grid_size = 16

input_grid = np.zeros((grid_size, grid_size))

# Draw the letter "H" on the input grid

# Horizontal line

input_grid[7, 3:12] = 1

# Vertical lines

input_grid[4:12, 3] = 1

input_grid[4:12, 12] = 1

# Create a 3x3 identity kernel

conv_kernel = np.array([[0, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 0]])

# Call the function to simulate convolution

simulate_convolution(input_grid, conv_kernel)

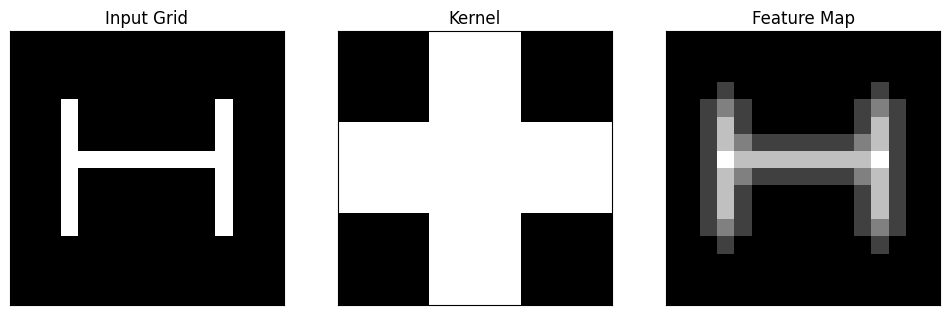

The result on the right is the same letter, what happens if we change the kernel to:

0.00 0.20 0.00

0.20 0.20 0.20

0.00 0.20 0.00# Create a 3x3 blur kernel

conv_kernel = np.array([[0, 0.2, 0],

[0.2, 0.2, 0.2],

[0, 0.2, 0]])

# Call the function to simulate convolution

simulate_convolution(input_grid, conv_kernel)

input_grid

[[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]]

kernel

[[0. 0.2 0. ]

[0.2 0.2 0.2]

[0. 0.2 0. ]]

feature_map

[[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0.2 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.2 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0.2 0.4 0.2 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.2 0.4 0.2 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0.2 0.6 0.2 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.2 0.6 0.2 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0.2 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.2 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0.2 0.8 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.8 0.2 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0.2 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.2 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0.2 0.6 0.2 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.2 0.6 0.2 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0.2 0.6 0.2 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.2 0.6 0.2 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0.2 0.4 0.2 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.2 0.4 0.2 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0.2 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.2 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. ]]The image is blurred right ? Now, as we change the kernel, the feature map will change accordingly.

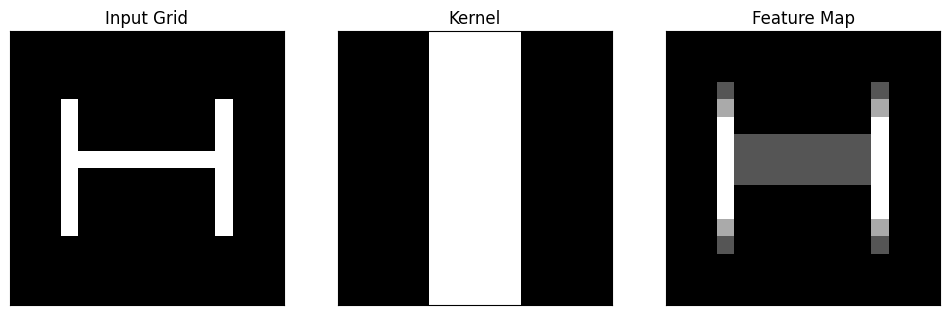

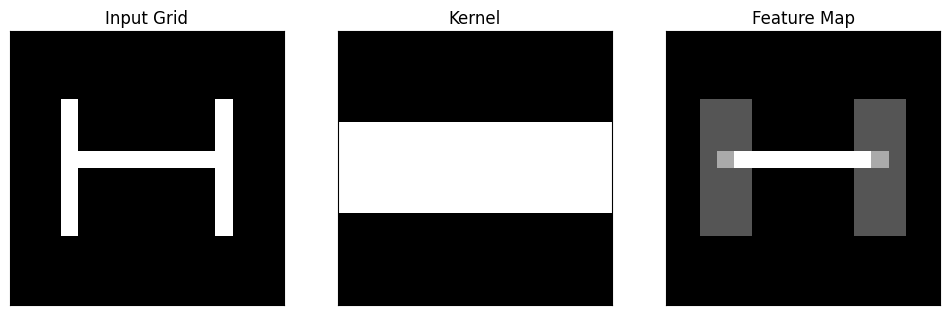

Can we use the kernel to detect horizontal line and vertical line ?

# Create a 3x3 vertical line detection kernel

conv_kernel = np.array([[0, 1, 0],

[0, 1, 0],

[0, 1, 0]])

# Call the function to simulate convolution

simulate_convolution(input_grid, conv_kernel)

input_grid

[[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]]

kernel

[[0 1 0]

[0 1 0]

[0 1 0]]

feature_map

[[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 2. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 2. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 3. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 3. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 3. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 3. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 3. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 3. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 3. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 3. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 3. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 3. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 3. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 3. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 2. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 2. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]]# Create a 3x3 vertical line detection kernel

conv_kernel = np.array([[0, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 1],

[0, 0, 0]])

# Call the function to simulate convolution

simulate_convolution(input_grid, conv_kernel)

input_grid

[[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]]

kernel

[[0 0 0]

[1 1 1]

[0 0 0]]

feature_map

[[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 1. 2. 3. 3. 3. 3. 3. 3. 3. 3. 2. 1. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]]Yes we can!

Again, we prepare a spreadsheet for a quick simulation of Convolution: GSheet Link

So you can try it for yourself, it’s much easier using Google Sheet. Remember to make a copy for your own use.

The input data to a convolutional layer is usually in 3-dimensions: height, width and depth. Height and weight clearly refers to the dimension of the image. But what about depth ? Depth here simply refers to the image channels, in the case of RGB it has a depth of 3, for grayscale image it has a depth of 1.

The convolution layer then takes the input and apply the kernel to an area of the image and a dot product is calculated between the input pixels and the kernel. The kernel size is usually 3x3 but it can be adjusted. A larger kernel naturally covers a larger area and better detect large shapes or objects but less adapt to detecting the finer details such as edges, corners or textures which are better performed with a small kernel.

Source: Hochschule Der Medien

Then how can we create a kernel matrix? Is it by hand or is there a way to create it automatically?

Well, it turns out we can define the kernel size, but the kernel matrix itself is learned by the CNN Neural Network. Here’s how it works:

We know that the kernel moves across the image, but how it moves and steps from one position to another is determined by a parameter known as “strides.”

Strides dictate the amount by which the kernel shifts its position as it scans the input data. Specifically, strides control both the horizontal and vertical movement of the kernel during the convolution operation.

Larger stepsizes yield a correspondingly smaller output. In the picture below filtering with stepsize of $ s = 2 $ is shown below filtering the same input with a stepsize of $ s = 1 $.

Padding is usually applied on the input image by adding additional rows and columns around its border before convolution starts.

The objective is to ensure that the convolution operation considers the pixels at the borders of the input image, preventing information loss and border effects.

The most commonly used padding is zero-padding because of its performance, simplicity, and computational efficiency. The technique involves adding zeros symmetrically around the edges of an input.

# using numpy to create 5x5 matrix, with random values

import numpy as np

# init random seed

np.random.seed(0)

a = np.random.rand(5, 5)

# print a nicely

np.set_printoptions(precision=3, suppress=True)

print("Original matrix")

print(a)

print()

# add 0 to the left and right of the matrix

b = np.pad(a, pad_width=1, mode='constant', constant_values=0)

print("After padding, p = 1")

print(b)

# we can also pad more than one row or column

c = np.pad(a, pad_width=2, mode='constant', constant_values=0)

print("After padding, p = 2")

print(c)Original matrix

[[0.549 0.715 0.603 0.545 0.424]

[0.646 0.438 0.892 0.964 0.383]

[0.792 0.529 0.568 0.926 0.071]

[0.087 0.02 0.833 0.778 0.87 ]

[0.979 0.799 0.461 0.781 0.118]]

After padding

[[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0.549 0.715 0.603 0.545 0.424 0. ]

[0. 0.646 0.438 0.892 0.964 0.383 0. ]

[0. 0.792 0.529 0.568 0.926 0.071 0. ]

[0. 0.087 0.02 0.833 0.778 0.87 0. ]

[0. 0.979 0.799 0.461 0.781 0.118 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. ]]

After padding

[[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0.549 0.715 0.603 0.545 0.424 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0.646 0.438 0.892 0.964 0.383 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0.792 0.529 0.568 0.926 0.071 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0.087 0.02 0.833 0.778 0.87 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0.979 0.799 0.461 0.781 0.118 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. ]

[0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. ]]We perform an Activation function after every convolutional layer in the network architecture.

The ReLU activation function is specifically used as a non-linear activation function, as opposed to other non-linear functions such as Sigmoid because it has been empirically observed that CNNs using ReLU are faster to train than their counterparts

Then how can we create a kernel matrix? Is it by hand or is there a way to create it automatically?

Well, it turns out we can define the kernel size, but the kernel matrix itself is learned by the CNN Neural Network. Here’s how it works:

The size of the output feature map is controlled by stride and padding.

\[ W_{out} = \frac{W_{in} - F + 2P}{S} + 1 \]